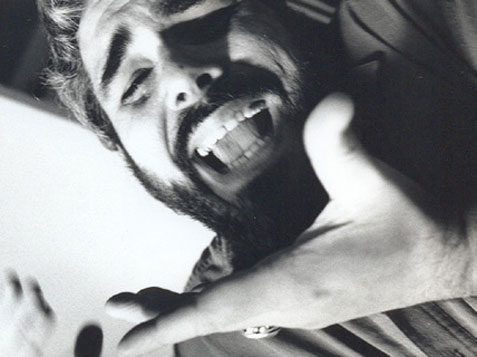

The 46th Tonspur (22.8. - 26.11.2011) is delivered by David Moss in context of a cooperation between Ö1 Kunstradio and Tonspur. David Moss is considered an extreme vocalist, exceptionally gifted percussionist and a central character of avantgarde sound art.

In his piece ’23 ways to remember silence – only one way to break it’ of which actually two versions exist – one Kunstradio only version and one Tonspur-Passage exclusive installation - David Moss combines his own texts of philosophical quality with extracts of soundscapes, improvised vocal performances and very special live-electronics giving us an idea of his memory.